The Stallman Paradox: How Web3 Became the Ultimate Open Source Theater

We Revere the Prophet, Yet Build the Exact System He Warned Us Against

Beyond Funding: Web3's Real Coordination Crisis and the Paradoxes We're Ignoring

'The uncomfortable truth is that funding, no matter how innovative or well-intentioned, cannot solve coordination problems rooted in unaddressed paradoxes.'

The Hidden Architecture of Human Systems: How Complexity Organizes Itself Through Tensegrity

How Dynamic Balance Shapes Everything From Relationships to Democracy

<100 subscribers

The Stallman Paradox: How Web3 Became the Ultimate Open Source Theater

We Revere the Prophet, Yet Build the Exact System He Warned Us Against

Beyond Funding: Web3's Real Coordination Crisis and the Paradoxes We're Ignoring

'The uncomfortable truth is that funding, no matter how innovative or well-intentioned, cannot solve coordination problems rooted in unaddressed paradoxes.'

The Hidden Architecture of Human Systems: How Complexity Organizes Itself Through Tensegrity

How Dynamic Balance Shapes Everything From Relationships to Democracy

This is Part 1 of the Social Architecture Series, where we build the sustainability infrastructure—Four Batteries and Hidden Factories—that every later governance and game‑theoretic mechanism design rests on.

I've spent the last three years studying organizational design across DAOs, tech nonprofits, and social enterprises. I've analyzed governance structures, incentive mechanisms, contributor workflows, and decision-making processes across dozens of organizations. What I kept finding was a consistent pattern: sophisticated governance designs failed to prevent burnout and turnover. Thoughtful mission statements didn't sustain commitment. Clear org charts didn't prevent dysfunction.

Then I realized I was studying the wrong level of architecture.

If you want the strategic overview of why game theory must be repositioned inside a wider governance frame, read “Governance Beyond Game Theory” and “What Lives Beneath the Mechanism” as precursors to this series.

All governance frameworks rest on a foundation nobody names. An infrastructure layer that determines whether any design actually works. This layer prevents workers from creating invisible workarounds to compensate for structural failures.

I'm calling it The Four Batteries.

The Four Batteries are the four dimensions of human capacity that must be actively managed or "charged" for organizations to remain sustainable:

Personal capacity—bandwidth and time boundaries;

Relational capacity—trust and communication;

Contribution capacity—clarity and alignment;

Inspiration capacity—connection to purpose.

When these four dimensions are deliberately managed from the beginning, workers remain intrinsically motivated and don't need to create Hidden Factories—the invisible systems of workaround and compensation that emerge when structural support is missing.

The Four Batteries are the inner sustainability infrastructure; they decide whether any outer governance structure—no matter how elegant—can actually be inhabited without burning people out.

Decentraland, ENS, Centrifuge, and Developer DAO—the most successful DAOs are building this infrastructure explicitly. Manage the Four Batteries before workers start creating invisible workarounds, and your governance works. Ignore them, and people will invent solutions themselves in unsustainable ways.

Work culture, especially in tech and mission-driven spaces, celebrates sacrifice. Working weekends. Boundless commitment. Burning out for the cause. This gets presented as a virtue. It's actually a systems design failure.

This is not a complaint about individual people. It's a description of what any normal human does when structures make it impossible to do good work in the open. If you recognize yourself in these patterns, that's not an accusation; it's evidence that you've been trying to keep things running inside architectures that make that nearly impossible.

When a worker encounters work that their official role doesn't cover, when support structures don't exist, they face a choice. They can say it's not their job. Or they can create an invisible workaround. Most people in mission-driven organizations create a workaround.

They start doing the work that the organization's structure doesn't account for. At first, this works. They're motivated. They care about the mission. The extra work gets done.

But here's what happens next: that invisible workaround becomes permanent. No one else knows how to do it. The worker becomes the only person who understands it. And now they own it. They can't leave it alone, or it will collapse. They can't hand it off because no one else knows what it is.

The organization benefits. The work gets done. But the worker is now running two jobs invisibly. One job is their official role. One job is the workaround they created to fill structural gaps. This invisible second job is what I'm calling the Hidden Factory.

It's work that shouldn't be necessary but is, because the organization's structure doesn't account for what actually needs to happen. The worker eventually burns out because they're doing impossible work. The organization acts shocked. Like something mysterious happened.

It's not mysterious. The organization created conditions in which workers had to invent solutions to structural problems. And then the organization benefited from those invisible solutions while the worker paid the cost.

The Four Batteries framework is about preventing workers from reaching the point where they start creating Hidden Factories. Every person who contributes to an organization carries four batteries that either charge or deplete, depending on the organization's structure.

When batteries collapse, people cannot reliably embody their actual developmental capacity; they regress under load, which is why the same mechanisms produce very different behaviors at different battery levels.

When batteries stay charged, workers remain intrinsically motivated and can sustain their work without creating invisible compensations. When batteries deplete, workers have no choice but to create workarounds to survive the structural failure.

The Personal Battery is your individual capacity—your physical, mental, and emotional bandwidth. It stays charged when scope is bounded, expectations are clear, and when you actively protect your own time and health. It depletes when the organization keeps expanding what's expected without adding resources or support, and when you stop protecting your own boundaries.

A charged Personal Battery means workers can actually sustain their effort without running invisible second jobs just to keep up. It also means you have the capacity to take care of yourself—sleep, exercise, relationships, recovery—instead of sacrificing everything to work.

The Relational Battery is trust. It's your belief that the people around you are competent, trustworthy, and aligned with you. It stays charged when communication is transparent, and conflict is addressed. It depletes when decisions are made behind closed doors and conflict is ignored.

A charged Relational Battery means workers don't have to create invisible advocacy systems or workarounds to protect themselves from organizational dysfunction.

The Contribution Battery is clarity about your work. It's knowing that what you do matters, aligns with what others are doing, and isn't duplicative. It stays charged when priorities are stable, and you understand the broader context. It depletes when priorities constantly shift, and you're not sure what actually matters.

A charged Contribution Battery means workers understand their role and don't have to invent invisible clarification systems.

The Inspiration Battery is your connection to purpose. It's knowing that your work matters beyond the immediate task and that the mission is real. It stays charged when progress is visible, and leaders embody the values they claim to care about. It depletes whenthe mission becomes secondary to survival.

A charged Inspiration Battery means workers stay motivated by the actual mission rather than creating invisible support systems just to believe in what they're doing.

These aren't motivational concepts. They're structural requirements. When all four batteries are charged, workers can sustain their intrinsic motivation. They contribute to the mission because the work matters and the system works. As batteries start to deplete, workers switch to creating workarounds. They start building Hidden Factories. They're still motivated by the mission, but now they're also compensating for structural failure. That's when burnout becomes inevitable.

There's a critical moment in every organization's development—the point where intrinsic motivation meets structural limits. Workers arrive excited about the mission. Their batteries are charged. They bring others in. They build peer support. Everything is working.

This is Stage A: Initial Motivation. Pure intrinsic drive, where ideas and excitement motivate workers naturally because support isn't yet needed. Other people support their efforts because saying yes doesn't cost them anything yet.

Then the organization hits the inflection point. There's no mentorship structure. No clear progression. No conflict resolution. No way to handle growth without scope exploding. The batteries start depleting.

Stage B: Research and Collaboration emerge. Workers bring in others seeking support and inspiration, encountering the natural diversity of human motivation. Some align with their vision. Others bring different perspectives, intensities, and purposes. This heterogeneity is not pathology—it's the healthy ecology of collaboration. The diversity becomes problematic only if the organization can't hold it with a real structure. At a small scale, it's informal. At the protocol scale, it requires governance clarity. At the institutional scale, it demands an explicit process. Without structure, batteries drain quietly.

Workers realize the organization's support structures don't match what they actually need. They start creating solutions invisibly. This is Stage C: Externalizing Intrinsic Motivation—the true inflection point.

They become unofficial mentors. They start advocating for others. They manage things the organization should manage. They design shadow onboarding, informal conflict resolution, and undocumented progression paths. Their Relational, Contribution, and Inspiration batteries are depleting, but they're overcompensating by externalizing what should be formal structure.

At this stage, organizations can still choose. Option one: Build structures intentionally before workers need to invent them. Create progression, bound scope, fund mentorship, and implement conflict resolution. Keep batteries charged. Option two: Ignore it. Let workers compensate. Benefit silently while workers pay.

When option two dominates, workers enter Stage D: Extending to Cover Structural Lack. A psychological paradox emerges.

Their energy is depleting. Hours are expanding. Sustainability is eroding. But simultaneously, they're experiencing something deeply rewarding—agency, ownership, meaningful contribution, which the official structure doesn't provide. This is Byung-Chul Han's achievement paradox: the impulse to over-contribute overrides rational cost-benefit calculation. The Hidden Factory feels like the real work. They have total context. No one else can do it. That indispensability feels good, even as it destroys them.

Energy costs escalate. Psychological rewards escalate. They're simultaneously exhausted and powerful. Other motivations mix in: desire for influence, fear of replacement, desperation to protect the mission. The paradox hardens: they feel worse physically while feeling more essential psychologically. Their Personal Battery drains while their sense of control fills the gap.

Stage E: Hidden Factory Ownership Becomes Permanent is where the paradox calcifies into identity.

What was dynamic becomes rigid. They can no longer separate themselves from the system they built. In Stage D, stepping back was theoretically possible. In Stage E, it's psychologically impossible. Their identity has fused with the Hidden Factory.

Someone suggesting improvements to their system feels like personal criticism. Someone taking over feels like erasure. They experience simultaneous relief (finally, help!) and threat (I'm losing who I am here). The factory is literal in their nervous system. It's not two separate jobs. It's "who I am." Their Relational Battery can't recover because the system is now part of self-protection. Their Contribution Battery is entirely occupied by protecting the workaround.

The organization is fully dependent. Even when leadership finally says, "We should formalize this," the worker struggles to let it go. Identity is too entangled.

Finally comes Stage F: Burnout, Security Violations, and Standards Erosion.

At this stage, complete collapse is approaching. The system they created to compensate is now breaking them and the organization. They cut corners just to survive. Not because they stopped caring about standards, but because exhaustion makes adherence impossible. All four batteries are depleted simultaneously. This is where mass departures happen. Not because workers lost faith in the mission, but because they exhausted themselves compensating for structural failure and cannot let go of the workarounds, which have become their identity.

When multiple people reach Stage F at once, multiple Hidden Factories collapse simultaneously. That's when organizations experience the "sudden" crisis. Governance freezes. Operations stall. Treasury is at risk. In reality, nothing sudden happened. Years of invisible compensation simply hit their absolute limit.

The stages A through F follow identical mechanics whether you're looking at a 5-person startup, a 100-person company, a protocol with thousands of stakeholders, a technology platform with billions of users, or a civilization-scale institution.

What changes with scale is the distribution of costs and consequences:

Scale | Stage C | Stage D | Stage E | Stage F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Small team | One person adapts; visible to all | Founder's identity fuses; still localized | Cannot delegate; team feels dependent | Burnout is obvious; recovery is hard but possible |

Medium org | Multiple departments compensate invisibly | Executive fuses; structural now | Cannot change without self-threat | Department crisis; leadership loss; possible recovery |

Large institution | Systemic workarounds across levels | Leader's judgment IS the system | Most resistant to change; maximum authority = maximum resistance | Institutional cascade; years to recover |

Civilization scale | Society runs compensatory systems | Leader at maximum control/visibility; maximum agency |

At the civilization scale (Twitter/X under Musk, AAVE Labs under identity-fused leadership), Stage F doesn't look like a collapse. It looks like society is running Hidden Factories to maintain stability despite institutional chaos. Employees maintain platform stability despite impossible directives. Advertisers maintain presence despite brand chaos. Researchers document degradation. Government forbears enforcement. Citizens run informal institutions to constrain excess. The Hidden Factory doesn't resolve through individual burnout. It resolves through systemic degradation—normalized dysfunction that everyone silently accepts.

This is where George Carlin's observation becomes essential.

Decades ago, Carlin identified the mechanism with crystalline clarity: "When your identity is your ideology, you cannot change your mind. Because changing your mind would mean changing who you are. And most people would rather die than change who they are." [See: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/dDJFH358dRg]

Carlin was observing civilization-scale systems—political ideology, religious belief, cultural narrative. But the mechanism he identified is structurally identical at every scale. In organizations, this same dynamic traps workers in Hidden Factories. Once they've identified themselves with the workaround they've created, they cannot release it—even though it's destroying them—because releasing it would mean releasing part of their identity.

What's remarkable is that Carlin made this observation decades ago. It resonated deeply enough that it became iconic. Yet almost no one has acted on the structural implications.

His companion observation—"It's a big club, and you ain't in it"—described the same pattern at the institutional scale: systems designed to extract value from non-members while making membership seem impossible. Those systems persist because the people who benefit from them have fused their identities with them. They cannot change the rules without changing who they are.

Carlin's job was to stand outside and roast the species. The job of this piece is the opposite: to give people who still care about organizations a clear language and set of levers to design our way out of this.

If this pattern matches what you're living, treat it not as a verdict but as a shared language we can use together.

There's a critical distinction between organizations that prevent burnout and those that suffer catastrophic collapse: healthy organizations don't try to eliminate Hidden Factories. They cycle through them consciously.

In a well-monitored organization, a worker beginning to create a Hidden Factory at Stage C triggers immediate recognition. This is not a failure. It's diagnostic information. The system is trying to tell you something important: "There's a structural gap here, and someone is compensating for it."

When this information surfaces—when leadership sees that conflict resolution is happening unofficially, or mentorship is occurring in shadow channels, or priority-setting is being done invisibly—the organization faces a choice. They can ignore it (letting Hidden Factories progress toward E and F). Or they can consciously engage with what's emerging.

This conscious engagement is what Deep Democracy calls "cycling."

In Deep Democracy, cycling happens when the same issue, behavior, or tension keeps reappearing in group discussions—typically three or more times. Cycling signals that the group is circling around an unspoken edge: something important that nobody has named yet.

Rather than treating cycling as a problem to eliminate, Deep Democracy practitioners treat it as information to follow. The cycle is the system trying to surface something crucial that consensus reality is avoiding.

When a group starts cycling, the Deep Democracy facilitator does two things:

First, they mark it explicitly. "I notice we're cycling on this same issue. We've been here three times now. That's not random. It means something important is being avoided."

Second, they invite the group to enter it consciously. "Let's slow down. Let's talk about what we're not yet saying. What's at the edge of what this group is willing to acknowledge?"

Applied to Hidden Factories: An organization starts cycling when the same structural gap keeps reappearing in different forms. Workers create informal mentorship because there's no formal structure. The organization adds a mentorship program. But workers still create shadow mentorship for things the program doesn't cover. Workers create informal priority-setting because clarity doesn't exist. Leaders insist priorities are clear. But workers keep inventing unofficial systems to figure out what actually matters.

This cycling is not a failure. It's the organization's attempt to surface what it won't officially acknowledge: "We have systematic structural gaps, and we're depending on workers to compensate for them."

When leadership marks and enters this cycle—when they stop pretending the structure is adequate and start asking what's actually needed—the cycle can shift. Not disappear, but transform from unconscious repetition into conscious processing.

Stage D and the Tensegrity Condition

What does "holding the Four Batteries" actually mean at the structural level? It means maintaining tensegrity. When a worker begins to extend themselves at Stage D—taking on work the organization's structure doesn't account for—they become like an expanding strut. The question is whether the organization provides continuous cables: recognition that this is happening, ongoing monitoring of what's being carried, and formal integration of the work into the organizational structure. With continuous tension held, the extended system cycles back down to healthy stages B and C. The work becomes visible, bounded, and supported. Without it, the cables snap. The worker extends further without restraint, the organization remains unaware of its dependency, and the system collapses toward fusion and silent harm.

Stage D is the inflection point where the tensegrity condition becomes explicit. The worker has begun extending. The system now faces a choice: will the organization maintain the cables?

Path A (Continuous Tension): The organization recognizes the worker's extension, monitors what they're carrying, and integrates it into formal structure. Continuous acknowledgment and support create the cables that hold the expanding strut in equilibrium. The system remains in dynamic balance, batteries stay charged, and the worker's extended capacity becomes organizational capacity. The cycle can then descend back to healthier stages where less extension is needed because structures are in place.

Path B (Broken Cables): The organization ignores the extension, normalizes the workaround, and leaves the worker to fend for themselves. Without organizational recognition and monitoring, there is no continuous tension. The strut extends further without restraint. The worker's identity fuses with the system they've created. Silent harms accumulate in the organization—undocumented processes, single points of failure, dependency risks that no one officially acknowledges. The system appears to work because the worker is compensating. But the cables are broken. Eventually, the system collapses catastrophically.

When we talk about Stage E—where Hidden Factory ownership calcifies into identity—we're describing something deeper than psychological attachment. We're describing a developmental regression.

Robert Kegan's core insight about human development is deceptively simple: growth happens through subject-object shifts. Healthy development means learning to see things you were once identified with as objects you can examine and change.

A young child is subject to their emotions—they ARE their anger, their joy. They can't see emotions as separate from the self.

As they develop, emotions become an object. "I'm experiencing anger. I can understand it, express it, choose how to respond to it." They're no longer fused with the emotion.

This subject-object shift—from being the emotion to having an emotion—is what developmental growth looks like across every domain.

Applied to Hidden Factories:

In Stages A and B, workers are subject to structural problems. "There's no mentorship. I experience that gap." But they can see the gap objectively. They can say, "This is a structural problem the organization should solve." They maintain differentiation between themselves and the problem.

In Stage C, workers start creating solutions. They're still somewhat differentiated. "I see the problem. I'm going to create an unofficial solution." The solution is still an object—something they're doing, not something they are.

But as they move into Stage D, something shifts. The solution becomes part of the subject. They begin to identify with it. "I'm the person who mentors people. I'm the one who handles conflicts. I'm the person who holds this together." The workaround is no longer something they do. It's who they are.

In Stage E, this fusion is complete. They can no longer distinguish between themselves and the Hidden Factory. The boundary collapses. Any threat to the system feels like a threat to the self. Any suggestion to change it feels like personal criticism. Any offer to take it over feels like erasure.

This is not a simple psychological attachment. This is a regression in developmental capacity. They've lost the ability to be subject to the system they created. They've become fused with it.

Conscious cycling prevents this regression by maintaining dialogue and perspective-taking capacity before fusion becomes identity.

Even with good intentions, organizations fail when the complexity of the work and the sensemaking “altitude” of the people holding it are out of sync. This section outlines a minimal vocabulary for recognizing misalignment before it becomes Hidden Factories.

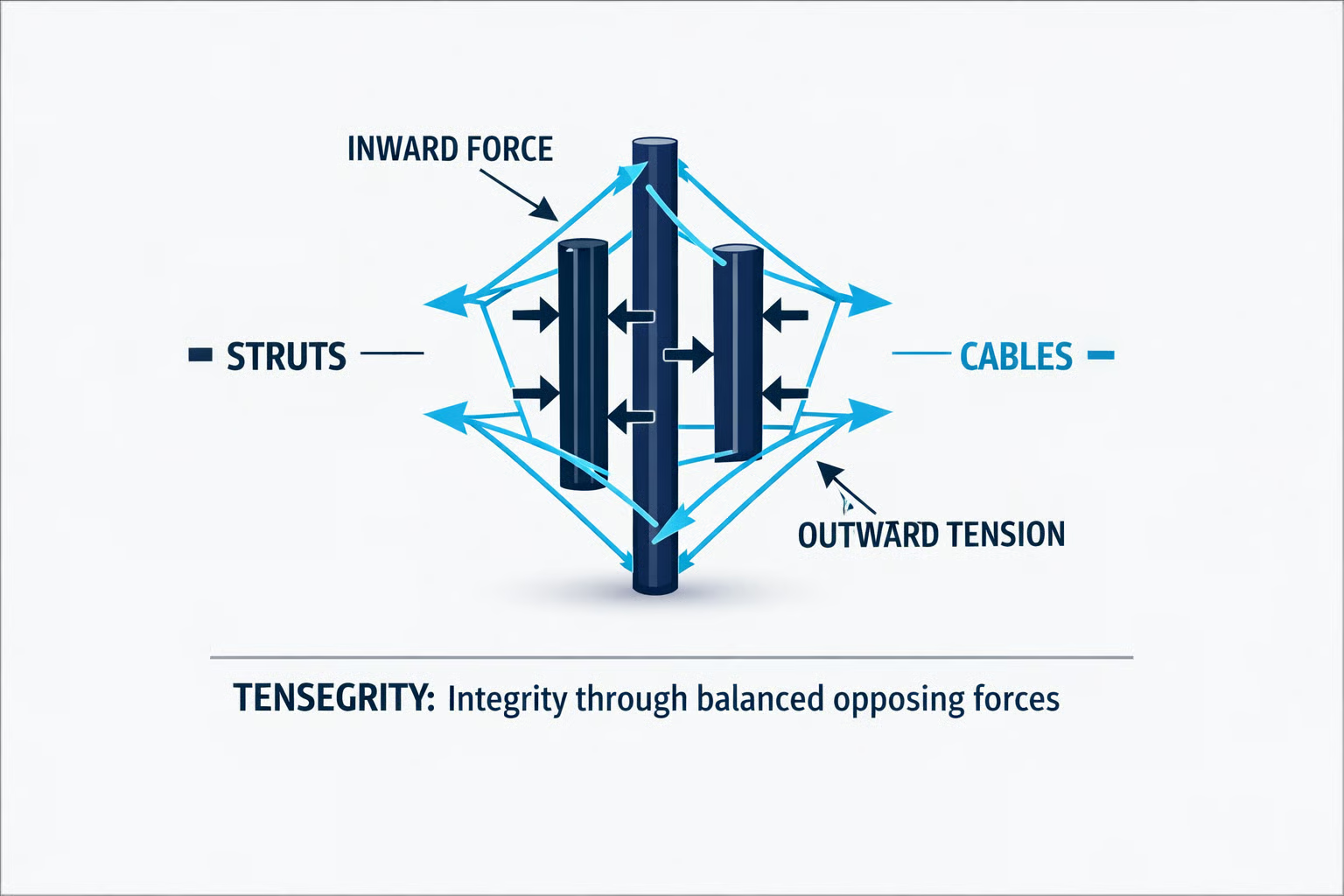

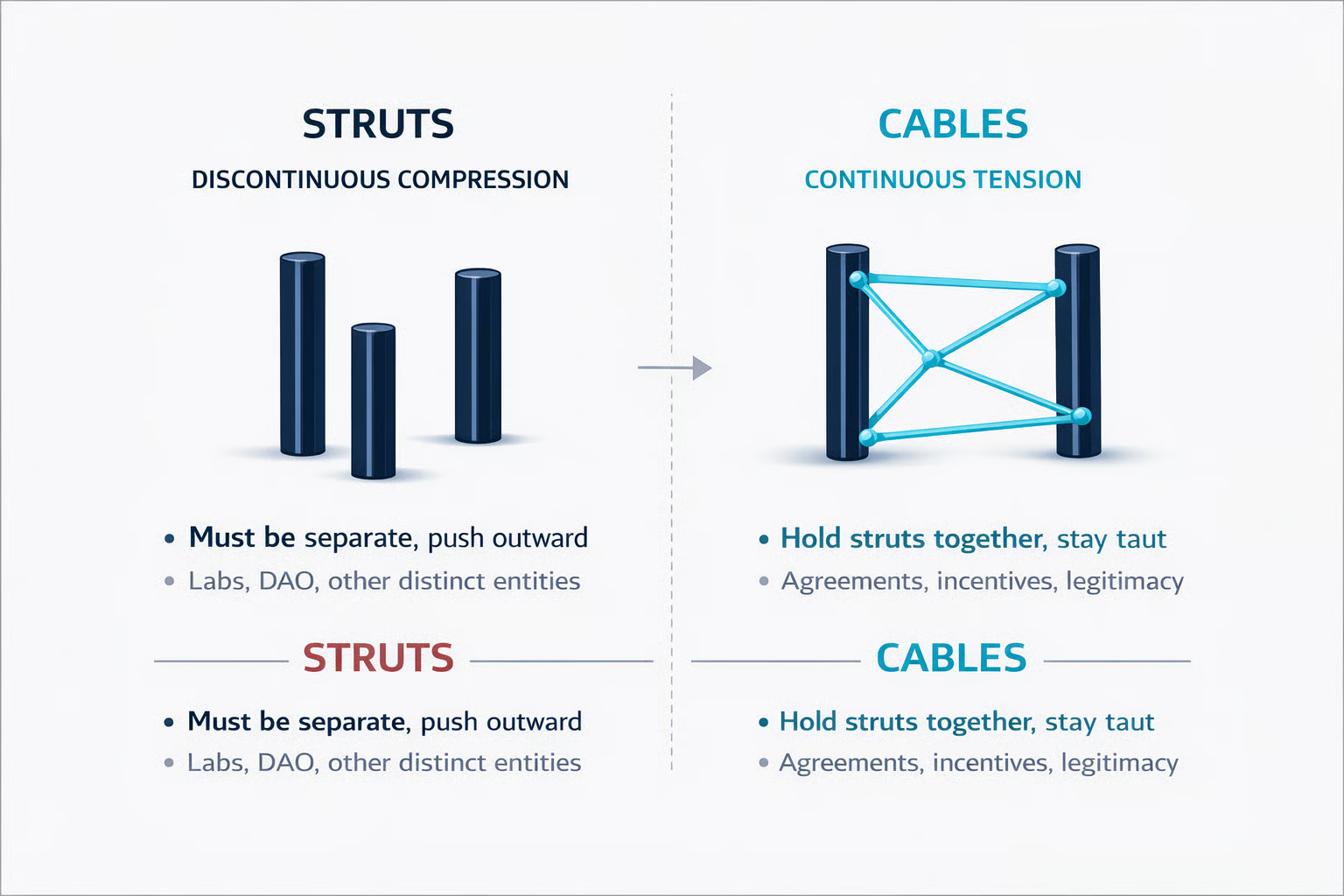

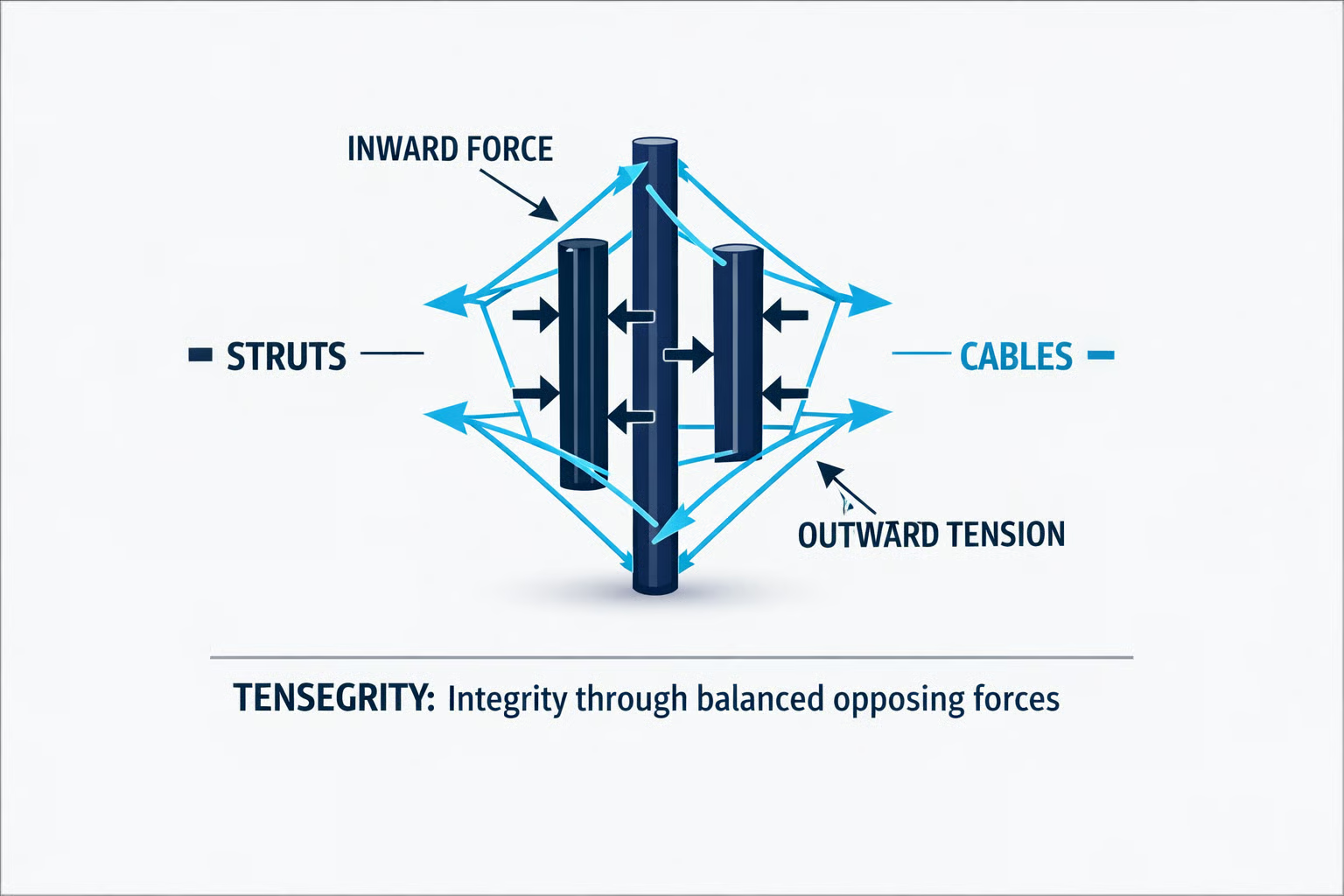

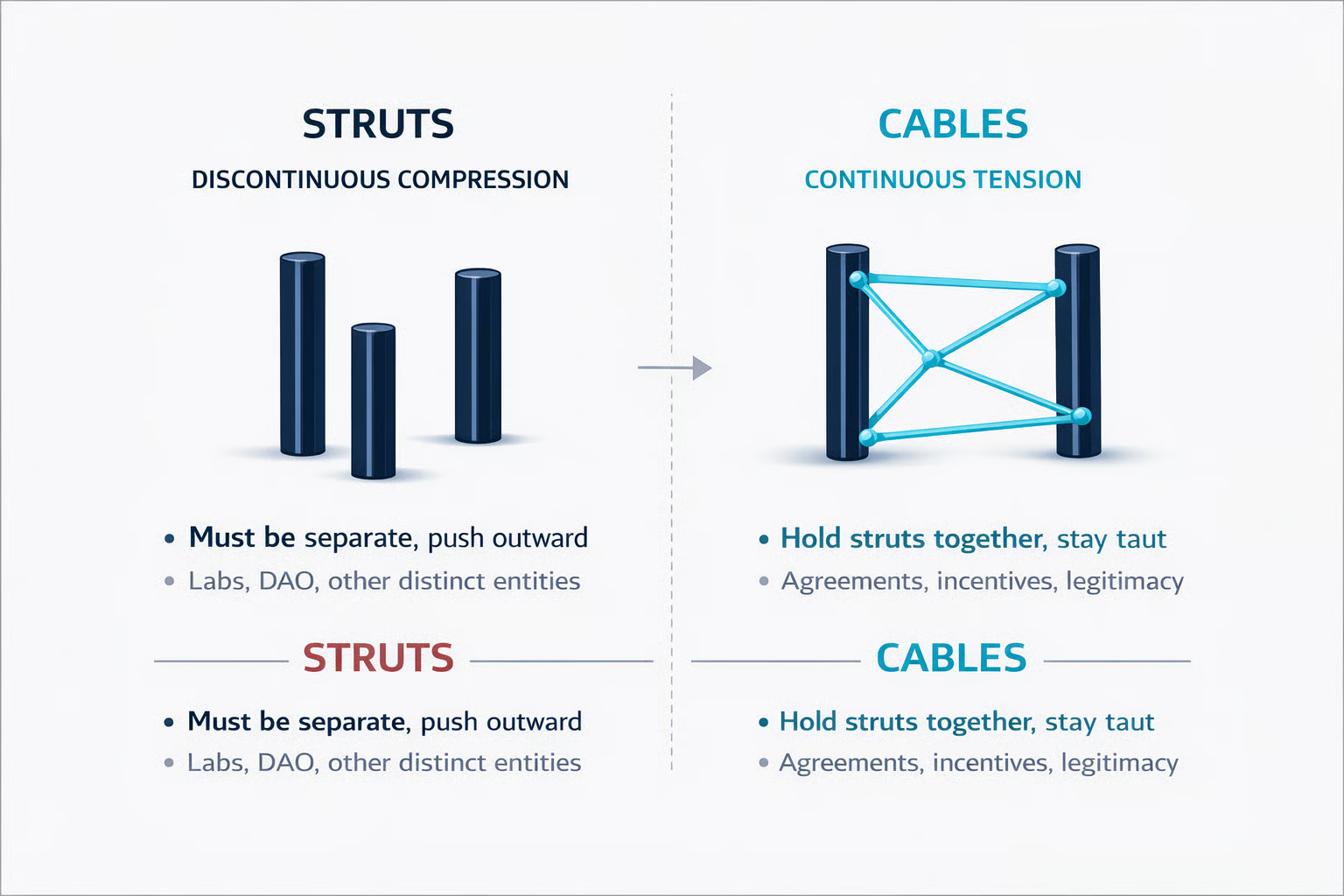

INTRODUCING TENSEGRITY: Integrity Through Balanced Forces

Organizations maintain integrity the way physical tensegrity structures do: through balanced opposing forces held in dynamic equilibrium. Tensegrity works through two complementary elements. Struts are discontinuous—they must remain separate and push outward, creating expansion and potential. Cables are continuous—they maintain tension, holding the struts together and preventing the system from flying apart. Neither element alone creates integrity. Struts without tension collapse into chaos. Cables without struts create stagnant compression. Integrity emerges from the dance between them: discrete elements pushing outward, held by continuous restraining force.

Different kinds of work live in different kinds of environments. Some are stable and rule-bound. Others are messy and fluid, with no obvious right answer. Complexity theorists often distinguish three basic types of environment in the Cynefin framework, often summarized as:

Clear: Cause and effect are obvious. There are known rules and best practices. If you follow the checklist, it works.

Complicated: Cause and effect are knowable but not obvious. You need expertise, analysis, and a good process to find a solution, but once you do, you can repeat it.

Complex: Cause and effect are only visible in hindsight. New patterns keep emerging. You have to probe, sense, and respond rather than apply a fixed playbook.

The Cynefin framework names these distinctions more formally, but for this piece, you only need the shorthand: clear work, complicated work, and complex work.

People also make sense of the world at different “altitudes” of meaning-making. Integral Theory uses colors as a shorthand for these altitudes. The colors are not value judgments; they are different toolkits for navigating reality.

When organizations break down, it is often because the altitude at which a worker can reliably operate does not match the complexity of the environment they are being asked to navigate or manage.

Blue in Clear environments functions fine. Orange in Complicated environments also works well.

But when Orange workers are dropped into Complex environments without Green–Yellow structures around them, Hidden Factories are almost guaranteed to appear. But when Orange workers are dropped into Complex environments without Green–Yellow structures around them, Hidden Factories are almost guaranteed to appear. By Green–Yellow structures, think concrete containers for relational and systemic work: funded facilitation and conflict resolution, real spaces for cross-team sensemaking, explicit roles for community care and governance, and decision processes that can hold multiple perspectives without forcing premature consensus.

Blue: Rule-based. The world makes sense when there are clear rules, roles, and procedures. The priority is doing things “the right way” and staying loyal to shared norms.

Orange: Strategic. The world is a system to optimize. The priority is analysis, innovation, and finding the most effective solution using data and expertise.

Green: Relational. The world is a web of perspectives. The priority is inclusion, dialogue, and caring about how decisions land on different people.

Yellow: Integrative. The world is many overlapping systems. The priority is holding conflicting truths at once and choosing structures that work across multiple perspectives.

In what follows, “altitude” simply means which of these toolkits someone can reliably use when things get difficult.

The most sophisticated monitoring doesn't just detect problems. It tracks something more fundamental: whether each worker's developmental capacity matches the complexity of the domain they're navigating.

There’s a structural relationship between the consciousness stages Integral Theory describes and the complexity of the environment you can navigate in Cynefin. Let’s connect them.

Blue consciousness ≅ Clear domain. Blues excel at execution in stable, well-defined environments. "Here are the rules. Follow them precisely. Consistency and loyalty are virtues." Clear domains reward this. Rules don't change. Procedures work reliably.

Orange consciousness ≅ : Complicated domain. Oranges excel at strategic problem-solving and innovation in domains with many moving parts but discoverable patterns. "We can optimize this. We can find the best solution through analysis and competition." Complicated domains need this—systems with expertise, best practices, competitive innovation.

Green consciousness ≅ Complex domain threshold. Greens add relational and collective sensitivity. "We need to include all perspectives. We need to consider human impact. We need a collective agreement." Green is the consciousness that can hold contradictions and include marginalized views, which complex domains require.

Yellow consciousness ≅ Complex domain mastery. Yellows can hold multiple systems simultaneously without needing to reduce them to one view. "All these perspectives are valid. They're contradictory AND both true. We can navigate this paradox." Yellow can naturally inhabit complexity.

Hidden Factories often emerge from misalignment between developmental capacity and complexity. For example, a worker with Orange consciousness—excellent at strategic thinking and innovation—is placed in a Complex domain without adequate Green-stage support structures.

Orange can see the problems (multiple perspectives, stakeholder needs, competing values). But Orange alone can't navigate them. That requires Green consciousness—relational depth, collective dialogue, and inclusion of marginalized perspectives.

Without Green structures to support them, the Orange workers compensate. They create unofficial listening systems (mentorship, conflict resolution, community care). They invent workarounds to include what formal structures exclude.

They're trying to provide Green-stage function from an Orange-stage capacity. This is taxing. This is unsustainable. And crucially, this prevents the worker from developing the Green capacity they're trying to access.

Instead of learning Green consciousness, they become fused with their Green-function workarounds (Stages D-E).

A healthy organization with capacity-complexity monitoring would catch this misalignment. They'd see: "This talented strategic thinker is having to provide all the relational and collective work that should be systemic. We need Green-stage structures so they can operate at Orange + access Green support rather than provide Green alone."

Some DAOs and protocols quietly solved the Hidden Factory problem by never letting it fully form. This section shows how six real organizations built Four‑Battery infrastructure early instead of relying on invisible overwork.

I'll highlight six successful DAOs here to use as relevant examples for this piece. What I found is that they all recognized the inflection point before Stage C fully formed. They all built structures intentionally before workers had to create Hidden Factories. They solve it differently. But they're all managing the same four batteries. And they're all doing it from the beginning to keep workers intrinsically motivated rather than resorting to workarounds.

Decentraland DAO uses transparent gatekeeping. To advance from one tier to the next, you have to pitch your contributions to voting power holders. They vote publicly. This creates clarity about progression before confusion sets in. You know what advancement means. You know who decides. You know you're part of the community's view of your work. This charges the Relational Battery and the Contribution Battery simultaneously. Workers don't have to create invisible advocacy systems to understand if they're valued.

ENS DAO uses bounded progression levels. You start with small bounties. If you prove yourself, you move to project grants. If you excel there, you become a core contributor. You can't jump levels. You can't go straight to governance. The progression is visible and the vetting is explicit at each step. This bounds the Personal Battery and creates clarity about the Contribution Battery before scope explodes. Workers know exactly what's expected and can plan their lives accordingly.

Built By DAO has nine levels with explicit scope at each level. An apprentice is expected to learn. A maker has bounded responsibility. A lead has defined scope. The point isn't a rigid hierarchy. The point is that people know exactly what's expected of them at their level. Before they have to invent workarounds to understand what their job actually is, the job is already defined. Before they have to create invisible systems to manage their time, their time is already bounded.

Developer DAO took a different approach by paying mentors and coordinators explicitly. They recognized that mentorship is work. It needs to happen. Most organizations expect it to happen because people care about the community. Developer DAO understood that when mentorship is volunteer work, it gets abandoned when crisis hits. So they funded it. When mentorship is paid, it happens consistently. Workers get the support they need before they have to invent invisible support systems.

Centrifuge DAO created a role called the Opportunity Master. This person manages the contributor list, follows up with people, helps them understand compensation and paths forward, makes personal introductions, and maps opportunities to specific people. One person explicitly manages human progression. Workers know someone is paying attention to their development. They don't have to create invisible advocacy systems to get noticed or understood.

Yearn Finance solved it through economic incentives. Strategists receive performance fees on what they build. They contribute a portion of those earnings to a collective fund for team initiatives. Now experts have direct incentive to support their team. Mentorship becomes rational rather than sacrificial. Workers don't have to invent invisible peer support systems because support is built into the economics.

These six organizations solved the battery management problem using different mechanisms. But they all did the same thing fundamentally—they recognized the inflection point and built structures before workers had to invent them. They prevented workers from reaching Stages C, D, E, and F.

Decentraland built transparency about progression. ENS built clear advancement pathways. Built By DAO built explicit scope definitions. Developer DAO built funded mentorship. Centrifuge built a human role to manage progression. Yearn built economic incentives for support. None of them waited. None of them assumed workers would create necessary structures invisibly. They all built intentionally.

Waiting to “see how things play out” is itself a design choice. This section traces what happens when organizations delay structural fixes until after workers have already built, owned, and fused with their Hidden Factories.

When organizations don't intentionally build structures, workers do. And that's when Hidden Factories form—and when the psychological attachment problem kicks in.

I proposed a four-tier system for GravityDAO. Clear progression. Mentorship gatekeeping. Bounded roles. Someone is managing capacity. It was exactly like what these successful DAOs are now building. I proposed it in year 4; too late.

By then, workers had already progressed through Stages C and D into Stage E. They had already been running Hidden Factories for months. They had already created workarounds to compensate for missing structures. They had already started owning invisible solutions and investing in those workarounds. The batteries were already depleted.

The structure I proposed was right. The timing was wrong.

This taught me something crucial: you can't rescue an organization from Hidden Factory mode with good design alone. You can't ask workers to give up their invisible workarounds once they've been using them for months and have identified with them. They've invested identity in these workarounds. The organization has become dependent on them. Both sides have too much to lose. The worker can't release what they've built because it's become part of who they are.

You have to build structures before workers get their identities tied to them.

As batteries start to deplete, workers begin creating Hidden Factories. First, they bring in collaborators. They're looking for peer support. They're trying to validate that what they're experiencing is real. They're hoping others will help shoulder the structural burden they're hitting. This is late Stage B transitioning to Stage C. Workers are still intrinsically motivated. They're just uncomfortable and seeking support that the organization won't provide.

Then they start externalizing their intrinsic motivation. They realize the organization's support structures don't match their needs. Mentorship doesn't exist. Progression isn't clear. Conflict isn't being handled. So they start creating invisible solutions to these problems. They become mentors to peers without it being an official role. They start advocating for other workers without it being part of their job. They start mediating conflicts that aren't their responsibility to mediate. This is Stage C—they're inventing workarounds. This is the inflection point. Workers are now running Hidden Factories. They're compensating for structural failure. They're still motivated by the mission, but now they're also exhausted from running two jobs.

As the worker continues, they enter Stage D: they extend their efforts to cover more gaps. Now they're not just compensating—they're owning. The Hidden Factory becomes their domain. They have authority over it because they created it. They feel a sense of control and purpose from being the only one who understands how this works. This sense of ownership and control can feel good, even as it's destroying them. The invisibility gives them a weird kind of power.

Then Stage E: they can't let go. Even if the organization finally says, "Yes, we see the problem. Let's legitimize this. Let's hire someone to do this officially. Let's take this burden off you," the worker struggles to release it. Because the Hidden Factory has become part of their identity. Someone suggesting improvements to their system feels like criticism. Someone taking over feels like they're being replaced or diminished. The worker experiences relief and threat simultaneously.

Once a worker starts running a Hidden Factory, they own it. No one else knows how to do it. No one else understands it. If the worker leaves, it collapses. The worker can't leave it. They can't hand it off. It's become part of their identity and their work. And the organization has become dependent on it. The organization benefits from this invisible work while the worker struggles to release it, even though it's destroying them.

Then the worker enters Stage F: they extend their Hidden Factory to cover other gaps, or they completely burn out. They keep adding to it. Keep adding responsibility. Keep compensating for structural failure. Until one day, they can't anymore.

SushiSwap founder Chef Nomi suddenly left. He didn't gradually disengage. He disappeared. He had been running an invisible Hidden Factory—holding the organization together through force of will. He had owned this role completely. When he stopped, the organization experienced that as betrayal rather than what it was: exhaustion and the need to finally escape what he could no longer release.

BanklessDAO published an article in April 2022 titled "Having the Hard Conversation: Building Better Compensation Models." They acknowledged that workers were running Hidden Factories. They called it the Dead Sea Effect. Good people leave because they've been compensating for structural failure, and they're exhausted. The DAO recognized the problem but didn't put in place structures to prevent it. They let workers keep running Hidden Factories while acknowledging that this was happening, which only intensified the psychological trap.

By early 2024, BanklessDAO announced: "The perpetuity of the DAO is now at risk." Multiple workers had left. Multiple Hidden Factories collapsed simultaneously. Multiple structural problems surfaced at once. The organization tried to implement better structures, but by then the damage was done. Workers who had been running Hidden Factories no longer trusted the organization. The organization's attempt to acknowledge and fix the problem came too late.

Ryan Sean Adams, a co-founder, stepped down in mid-2024. He had been running perhaps the largest Hidden Factory—holding the mission together, connecting the organization to the broader narrative, maintaining the culture. This was deeply connected to his identity. When he burned out and left, it became obvious what he had been invisibly carrying.

Later, he took a complete 90-day sabbatical. He described it this way: "I had crashed. My mental system seemed to have collapsed. I had to delete every app, cut all obligations, and stop trying to optimize. Only then could I recover." He had to destroy his entire system of engagement to finally release what he couldn't hand off to anyone else. He couldn't just give it to the organization. He had to demolish it completely to recover.

By late 2024, the BanklessDAO community designed Black Flag DAO. Better structure. Clearer governance. Constitutional foundation. Community consensus for the change. But the old multisig holders refused to hand over power. The elected new governance couldn't be implemented because the organization's Hidden Factories of power were too entrenched. People at the highest level were running Hidden Factories of influence and control that they couldn't release, even when the organization was designed to help them let go.

One of the new Flag Keepers gave up. He wrote: "It's simply too difficult and stressful to try to revive and grow a DAO with this unresolved situation in the background." Even perfect new structures couldn't overcome the damage from years of Hidden Factories, and the psychological attachment workers had developed to them.

When Hidden Factories already exist, you can’t fix everything with one big structural change. This section provides a stage-specific playbook: what to do differently at A–F rather than treating all burnout as the same problem.

When batteries deplete and Hidden Factories form, recovery requires moving systematically from problem to solution. But the process differs dramatically depending on which stage you're in.

Step 1: Encourage Innovation (Recovery from Stage A-B)

If you catch this early, when workers are still intrinsically motivated, and heterogeneity hasn't yet forced invisible compensation, the solution is simple. Create space for the diversity that's already trying to emerge. Structure transparency around different motivations. Different people will contribute differently. That's healthy. Let it be visible. Create processes that value different kinds of contributions equally. Keep the Inspiration Battery charged by celebrating the richness of motivation rather than demanding uniformity.

Step 2: Ensure Workers Are Not Alone (Recovery from Stage B-C)

If you're in Stage B, approaching Stage C—workers are starting to feel unsupported but haven't yet fully externalized—create peer and mentorship structures before workers have to invent them. The Relational Battery needs active support. A peer/buddy system. Regular check-ins. Explicit mentorship roles. When people feel genuinely seen and supported, they don't need to create shadow systems.

Step 3: Create Process/Policy for Surfacing the Hidden (Recovery from Stage C)

If workers are already in Stage C—creating unofficial workarounds—your urgent task is legitimation. Create formal processes that surface what was invisible. "We see that conflict resolution is happening unofficially. Let's make it official. Let's fund it. Let's make it a real role." The Contribution Battery needs clarity. Undocumented processes need documentation. Shadow roles need formal recognition.

This is the critical intervention point. Workers in Stage C haven't yet deeply identified with their workarounds. You can still help them let it go—if you legitimize it, fund it, and take responsibility for it. Success rate at this stage: 80%. Cost: 3-5 units of resource. Timeline: 6-12 months.

If workers are in Stage D—they’ve started identifying with their Hidden Factory—the psychological dynamic changes. They’re not just compensating anymore. They’re owning.

Reclaiming ownership means helping them understand that what they’ve built is valuable and that they shouldn’t have had to build it in the first place. The organization accepts responsibility for structural failure. Workers begin the psychological work of separating identity from workaround.

This requires more than structural change. It requires psychological support. Workers may feel relief and threat simultaneously. They may experience the formalization of their workaround as a loss. Coaching, counseling, or peer support may be necessary.

Success rate at this stage: 50–70%

Cost: 10–15 units of resource

Timeline: 12–24 months

If workers are in Stage E—ownership has ossified into identity—recovery is fundamentally different. The Hidden Factory is now so fused with the worker that even organizational legitimation doesn’t trigger release.

At this stage, you’re not trying to convince someone to “let go.” You’re trying to help them see that the thing they’ve built—that’s become part of who they are—is actually destroying them. This might require external facilitation. It might require the worker to take a complete sabbatical to break the identity-fusion. It might require a leadership transition.

The goal is to interrupt the psychological loop where releasing the Hidden Factory feels like self‑annihilation. This often means the person needs to step back completely to recover.

Success rate at this stage: <30%

Cost: 20–50 units of resource

Timeline: ~24 months

If workers have burned out and the Hidden Factories have collapsed, the organization faces multiple simultaneous failures. Security is compromised. Standards have eroded. Trust is destroyed. The organization now has both structural failure and loss of institutional knowledge.

At this stage, you’re not recovering individual workers. You’re rebuilding the organization. The path forward requires:

Explicit acknowledgment of what happened and why.

Structural redesign to prevent recurrence.

Potential leadership transition if Stage E people remain in power.

Long-term investment in the infrastructure that should have existed from the beginning.

The Four Batteries are not just a design metaphor; they double as a simple diagnostic. Each depleted battery produces its own class of Hidden Factories, which you can spot by the kinds of invisible work people start doing.

Your organization is likely creating Hidden Factories if you see these patterns. Every depleted battery tends to generate its own class of invisible workaround.

Workers will create invisible time-management systems, off‑books productivity rituals, and shadow scheduling. They’re trying to protect their capacity, even though the organization won’t.

Ask:

Is the scope clear?

Are time expectations set?

Or are workers having to invent invisible boundaries?

Are workers sacrificing their own health and recovery to compensate?

Workers will create invisible advocacy systems, shadow networks, and workaround communication channels. They’re trying to build trust when the organization won’t create transparent processes.

Ask:

Is communication transparent?

Is conflict addressed?

Or are workers creating side channels to get real information?

Workers will create invisible priority systems, shadow project management, and undocumented decision-making processes. They’re trying to clarify the actual work, even though the organization won’t define it.

Ask:

Are priorities stable?

Is the connection to the mission clear?

Or are workers inventing workarounds to figure out what actually matters?

Workers will create invisible meaning systems, personal mission narratives, and shadow value structures. They’re trying to believe in the work, even though the organization won’t demonstrate progress toward its mission.

Ask:

Is the mission still central?

Are leaders embodying values?

Is progress visible?

Or are workers creating invisible justifications for why they’re here?

The pattern is clear: every depleted battery becomes a Hidden Factory. Workers don’t stop caring. They start compensating. And once they start compensating, they risk becoming psychologically attached to their workarounds in ways that make recovery even harder.

Prevention is not just morally nicer; it is orders of magnitude cheaper and more effective. This section sketches the rough cost and probability curve for intervening at each stage from A through F.

Recovery from Hidden Factories gets exponentially more expensive—and less likely—the later you intervene.

Prevent entirely (Stage A–B)

Cost: 1 unit

Time: 3–6 months

Success: ~95%

Intervene at Stage C

Cost: 3–5 units

Time: 6–12 months

Success: ~80%

Intervene at Stage D–E

Cost: 10–15 units

Time: 12–24 months

Success: 50–70%

Recover from Stage F

Cost: 20–50 units

Time: ~24 months

Success: <30%

The manufacturing principle applies: the cost of preventing problems is always lower than the cost of fixing them after they’ve created damage.

If you’re building an organization, recognize the inflection point before it arrives. Don’t wait until workers start creating Hidden Factories. Build mentorship structures before people are confused. Build progression pathways before people are unclear about advancement. Build conflict resolution before tensions become toxic. Build scope boundaries before everyone is doing everything. Keep workers in Stages A and B, where they remain intrinsically motivated.

If you’re in an organization experiencing Hidden Factories, the solution is to surface them and then own them. Create processes and policies that legitimize what was invisible. But understand that helping workers give up their invisible workarounds may require psychological support, not just structural change. Workers have identified with their workarounds. They may feel threatened by the organization finally addressing the structural problem. You have to help workers release what they’ve created, not just take it from them.

Have the organization accept responsibility for structural failure. Rebuild with intention. And explicitly support workers in releasing the psychological attachment to their workarounds.

If you’re a worker running Hidden Factories, recognize that this is unsustainable. The organization’s structural failure is not your responsibility to solve alone. You can surface the problem. You can help design solutions. But you can’t keep compensating for structural failure indefinitely. Your intrinsic motivation will eventually run out.

Protecting your own health and capacity—your Personal Battery—is not selfish. It’s essential. But also recognize this: you may have become psychologically attached to your Hidden Factory. You may feel protective of it. You may feel like releasing it means losing part of your identity or your purpose. That’s not a weakness. That’s a natural human response to something you’ve built and owned. But it’s also a trap. Your Hidden Factory is destroying you.

Releasing it—with support from the organization and possibly from counseling or coaching—is not failure. It’s recovery.

For each battery, ask honestly:

Personal Battery

Is the scope clear before workers have to invent it?

Are time expectations set before people scramble to figure them out?

Is someone managing capacity intentionally? Or are workers creating invisible scheduling systems?

Do workers have time and permission to take care of their own health and recovery?

Are workers showing signs of moving from Stage B to Stage C—starting to create invisible workarounds?

Relational Battery

Is communication transparent?

Is conflict addressed quickly?

Is the power structure clear?

Do workers trust that decisions are being made fairly?

Or are workers creating shadow networks to get real information?

Contribution Battery

Are priorities stable?

Does it work without constant invisible workarounds?

Is the connection between individual work and organizational mission obvious?

Or are workers creating invisible clarification systems?

Inspiration Battery

Is the mission still central?

Do leaders embody the values?

Is progress visible?

Are workers inspired—or creating invisible meaning systems to justify their effort?

If you answered honestly, you probably know where your organization stands. If all four batteries are charged, workers are intrinsically motivated and staying in Stages A and B. They’re not creating Hidden Factories.

If any battery is depleted, workers are probably already in Stage C or beyond—creating invisible workarounds, and potentially becoming psychologically attached to them. The question is whether you’ll acknowledge this and build structures, or whether you’ll let workers keep compensating for structural failure until they burn out and can’t even release what they’ve built.

Hidden Factories are what workers create when organizations fail to build necessary structures. They start as compensation for structural failure. They become identity. They become impossible to release.

The Four Batteries framework is about preventing the conditions that force workers to create Hidden Factories in the first place. Build battery management from the beginning. Build mentorship before it becomes volunteer burnout. Build progression before people are confused. Build clarity before the scope explodes. Build conflict resolution before trust erodes.

We are not going to rewrite human psychology. We can, however, redesign the architectures that either weaponize it or protect it. The Four Batteries framework is an invitation: map one Hidden Factory, run one honest conversation about where identity has fused with “how we do things here,” and start designing structures where change doesn’t feel like self-annihilation.

If this pattern matches what you’re living, treat this not as a verdict but as shared language we can use together to collaborate our way out of this mess. Build structures before workers have to invent them. Acknowledge when you haven’t. Help workers release what they’ve built. Support them through the psychological and structural dimensions of recovery.

That’s the only path to sustainable organizations. And it starts with understanding what the Four Batteries actually are, why they matter, and what happens when we ignore them.

CALL TO ACTION:

If you would like to join a working group focused on finding ways to measure, monitor, or anything else for any of these four sections, please let me know.

This is Part 1 of the Social Architecture Series, where we build the sustainability infrastructure—Four Batteries and Hidden Factories—that every later governance and game‑theoretic mechanism design rests on.

I've spent the last three years studying organizational design across DAOs, tech nonprofits, and social enterprises. I've analyzed governance structures, incentive mechanisms, contributor workflows, and decision-making processes across dozens of organizations. What I kept finding was a consistent pattern: sophisticated governance designs failed to prevent burnout and turnover. Thoughtful mission statements didn't sustain commitment. Clear org charts didn't prevent dysfunction.

Then I realized I was studying the wrong level of architecture.

If you want the strategic overview of why game theory must be repositioned inside a wider governance frame, read “Governance Beyond Game Theory” and “What Lives Beneath the Mechanism” as precursors to this series.

All governance frameworks rest on a foundation nobody names. An infrastructure layer that determines whether any design actually works. This layer prevents workers from creating invisible workarounds to compensate for structural failures.

I'm calling it The Four Batteries.

The Four Batteries are the four dimensions of human capacity that must be actively managed or "charged" for organizations to remain sustainable:

Personal capacity—bandwidth and time boundaries;

Relational capacity—trust and communication;

Contribution capacity—clarity and alignment;

Inspiration capacity—connection to purpose.

When these four dimensions are deliberately managed from the beginning, workers remain intrinsically motivated and don't need to create Hidden Factories—the invisible systems of workaround and compensation that emerge when structural support is missing.

The Four Batteries are the inner sustainability infrastructure; they decide whether any outer governance structure—no matter how elegant—can actually be inhabited without burning people out.

Decentraland, ENS, Centrifuge, and Developer DAO—the most successful DAOs are building this infrastructure explicitly. Manage the Four Batteries before workers start creating invisible workarounds, and your governance works. Ignore them, and people will invent solutions themselves in unsustainable ways.

Work culture, especially in tech and mission-driven spaces, celebrates sacrifice. Working weekends. Boundless commitment. Burning out for the cause. This gets presented as a virtue. It's actually a systems design failure.

This is not a complaint about individual people. It's a description of what any normal human does when structures make it impossible to do good work in the open. If you recognize yourself in these patterns, that's not an accusation; it's evidence that you've been trying to keep things running inside architectures that make that nearly impossible.

When a worker encounters work that their official role doesn't cover, when support structures don't exist, they face a choice. They can say it's not their job. Or they can create an invisible workaround. Most people in mission-driven organizations create a workaround.

They start doing the work that the organization's structure doesn't account for. At first, this works. They're motivated. They care about the mission. The extra work gets done.

But here's what happens next: that invisible workaround becomes permanent. No one else knows how to do it. The worker becomes the only person who understands it. And now they own it. They can't leave it alone, or it will collapse. They can't hand it off because no one else knows what it is.

The organization benefits. The work gets done. But the worker is now running two jobs invisibly. One job is their official role. One job is the workaround they created to fill structural gaps. This invisible second job is what I'm calling the Hidden Factory.

It's work that shouldn't be necessary but is, because the organization's structure doesn't account for what actually needs to happen. The worker eventually burns out because they're doing impossible work. The organization acts shocked. Like something mysterious happened.

It's not mysterious. The organization created conditions in which workers had to invent solutions to structural problems. And then the organization benefited from those invisible solutions while the worker paid the cost.

The Four Batteries framework is about preventing workers from reaching the point where they start creating Hidden Factories. Every person who contributes to an organization carries four batteries that either charge or deplete, depending on the organization's structure.

When batteries collapse, people cannot reliably embody their actual developmental capacity; they regress under load, which is why the same mechanisms produce very different behaviors at different battery levels.

When batteries stay charged, workers remain intrinsically motivated and can sustain their work without creating invisible compensations. When batteries deplete, workers have no choice but to create workarounds to survive the structural failure.

The Personal Battery is your individual capacity—your physical, mental, and emotional bandwidth. It stays charged when scope is bounded, expectations are clear, and when you actively protect your own time and health. It depletes when the organization keeps expanding what's expected without adding resources or support, and when you stop protecting your own boundaries.

A charged Personal Battery means workers can actually sustain their effort without running invisible second jobs just to keep up. It also means you have the capacity to take care of yourself—sleep, exercise, relationships, recovery—instead of sacrificing everything to work.

The Relational Battery is trust. It's your belief that the people around you are competent, trustworthy, and aligned with you. It stays charged when communication is transparent, and conflict is addressed. It depletes when decisions are made behind closed doors and conflict is ignored.

A charged Relational Battery means workers don't have to create invisible advocacy systems or workarounds to protect themselves from organizational dysfunction.

The Contribution Battery is clarity about your work. It's knowing that what you do matters, aligns with what others are doing, and isn't duplicative. It stays charged when priorities are stable, and you understand the broader context. It depletes when priorities constantly shift, and you're not sure what actually matters.

A charged Contribution Battery means workers understand their role and don't have to invent invisible clarification systems.

The Inspiration Battery is your connection to purpose. It's knowing that your work matters beyond the immediate task and that the mission is real. It stays charged when progress is visible, and leaders embody the values they claim to care about. It depletes whenthe mission becomes secondary to survival.

A charged Inspiration Battery means workers stay motivated by the actual mission rather than creating invisible support systems just to believe in what they're doing.

These aren't motivational concepts. They're structural requirements. When all four batteries are charged, workers can sustain their intrinsic motivation. They contribute to the mission because the work matters and the system works. As batteries start to deplete, workers switch to creating workarounds. They start building Hidden Factories. They're still motivated by the mission, but now they're also compensating for structural failure. That's when burnout becomes inevitable.

There's a critical moment in every organization's development—the point where intrinsic motivation meets structural limits. Workers arrive excited about the mission. Their batteries are charged. They bring others in. They build peer support. Everything is working.

This is Stage A: Initial Motivation. Pure intrinsic drive, where ideas and excitement motivate workers naturally because support isn't yet needed. Other people support their efforts because saying yes doesn't cost them anything yet.

Then the organization hits the inflection point. There's no mentorship structure. No clear progression. No conflict resolution. No way to handle growth without scope exploding. The batteries start depleting.

Stage B: Research and Collaboration emerge. Workers bring in others seeking support and inspiration, encountering the natural diversity of human motivation. Some align with their vision. Others bring different perspectives, intensities, and purposes. This heterogeneity is not pathology—it's the healthy ecology of collaboration. The diversity becomes problematic only if the organization can't hold it with a real structure. At a small scale, it's informal. At the protocol scale, it requires governance clarity. At the institutional scale, it demands an explicit process. Without structure, batteries drain quietly.

Workers realize the organization's support structures don't match what they actually need. They start creating solutions invisibly. This is Stage C: Externalizing Intrinsic Motivation—the true inflection point.

They become unofficial mentors. They start advocating for others. They manage things the organization should manage. They design shadow onboarding, informal conflict resolution, and undocumented progression paths. Their Relational, Contribution, and Inspiration batteries are depleting, but they're overcompensating by externalizing what should be formal structure.

At this stage, organizations can still choose. Option one: Build structures intentionally before workers need to invent them. Create progression, bound scope, fund mentorship, and implement conflict resolution. Keep batteries charged. Option two: Ignore it. Let workers compensate. Benefit silently while workers pay.

When option two dominates, workers enter Stage D: Extending to Cover Structural Lack. A psychological paradox emerges.

Their energy is depleting. Hours are expanding. Sustainability is eroding. But simultaneously, they're experiencing something deeply rewarding—agency, ownership, meaningful contribution, which the official structure doesn't provide. This is Byung-Chul Han's achievement paradox: the impulse to over-contribute overrides rational cost-benefit calculation. The Hidden Factory feels like the real work. They have total context. No one else can do it. That indispensability feels good, even as it destroys them.

Energy costs escalate. Psychological rewards escalate. They're simultaneously exhausted and powerful. Other motivations mix in: desire for influence, fear of replacement, desperation to protect the mission. The paradox hardens: they feel worse physically while feeling more essential psychologically. Their Personal Battery drains while their sense of control fills the gap.

Stage E: Hidden Factory Ownership Becomes Permanent is where the paradox calcifies into identity.

What was dynamic becomes rigid. They can no longer separate themselves from the system they built. In Stage D, stepping back was theoretically possible. In Stage E, it's psychologically impossible. Their identity has fused with the Hidden Factory.

Someone suggesting improvements to their system feels like personal criticism. Someone taking over feels like erasure. They experience simultaneous relief (finally, help!) and threat (I'm losing who I am here). The factory is literal in their nervous system. It's not two separate jobs. It's "who I am." Their Relational Battery can't recover because the system is now part of self-protection. Their Contribution Battery is entirely occupied by protecting the workaround.

The organization is fully dependent. Even when leadership finally says, "We should formalize this," the worker struggles to let it go. Identity is too entangled.

Finally comes Stage F: Burnout, Security Violations, and Standards Erosion.

At this stage, complete collapse is approaching. The system they created to compensate is now breaking them and the organization. They cut corners just to survive. Not because they stopped caring about standards, but because exhaustion makes adherence impossible. All four batteries are depleted simultaneously. This is where mass departures happen. Not because workers lost faith in the mission, but because they exhausted themselves compensating for structural failure and cannot let go of the workarounds, which have become their identity.

When multiple people reach Stage F at once, multiple Hidden Factories collapse simultaneously. That's when organizations experience the "sudden" crisis. Governance freezes. Operations stall. Treasury is at risk. In reality, nothing sudden happened. Years of invisible compensation simply hit their absolute limit.

The stages A through F follow identical mechanics whether you're looking at a 5-person startup, a 100-person company, a protocol with thousands of stakeholders, a technology platform with billions of users, or a civilization-scale institution.

What changes with scale is the distribution of costs and consequences:

Scale | Stage C | Stage D | Stage E | Stage F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Small team | One person adapts; visible to all | Founder's identity fuses; still localized | Cannot delegate; team feels dependent | Burnout is obvious; recovery is hard but possible |

Medium org | Multiple departments compensate invisibly | Executive fuses; structural now | Cannot change without self-threat | Department crisis; leadership loss; possible recovery |

Large institution | Systemic workarounds across levels | Leader's judgment IS the system | Most resistant to change; maximum authority = maximum resistance | Institutional cascade; years to recover |

Civilization scale | Society runs compensatory systems | Leader at maximum control/visibility; maximum agency |

At the civilization scale (Twitter/X under Musk, AAVE Labs under identity-fused leadership), Stage F doesn't look like a collapse. It looks like society is running Hidden Factories to maintain stability despite institutional chaos. Employees maintain platform stability despite impossible directives. Advertisers maintain presence despite brand chaos. Researchers document degradation. Government forbears enforcement. Citizens run informal institutions to constrain excess. The Hidden Factory doesn't resolve through individual burnout. It resolves through systemic degradation—normalized dysfunction that everyone silently accepts.

This is where George Carlin's observation becomes essential.

Decades ago, Carlin identified the mechanism with crystalline clarity: "When your identity is your ideology, you cannot change your mind. Because changing your mind would mean changing who you are. And most people would rather die than change who they are." [See: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/dDJFH358dRg]

Carlin was observing civilization-scale systems—political ideology, religious belief, cultural narrative. But the mechanism he identified is structurally identical at every scale. In organizations, this same dynamic traps workers in Hidden Factories. Once they've identified themselves with the workaround they've created, they cannot release it—even though it's destroying them—because releasing it would mean releasing part of their identity.

What's remarkable is that Carlin made this observation decades ago. It resonated deeply enough that it became iconic. Yet almost no one has acted on the structural implications.

His companion observation—"It's a big club, and you ain't in it"—described the same pattern at the institutional scale: systems designed to extract value from non-members while making membership seem impossible. Those systems persist because the people who benefit from them have fused their identities with them. They cannot change the rules without changing who they are.

Carlin's job was to stand outside and roast the species. The job of this piece is the opposite: to give people who still care about organizations a clear language and set of levers to design our way out of this.

If this pattern matches what you're living, treat it not as a verdict but as a shared language we can use together.

There's a critical distinction between organizations that prevent burnout and those that suffer catastrophic collapse: healthy organizations don't try to eliminate Hidden Factories. They cycle through them consciously.

In a well-monitored organization, a worker beginning to create a Hidden Factory at Stage C triggers immediate recognition. This is not a failure. It's diagnostic information. The system is trying to tell you something important: "There's a structural gap here, and someone is compensating for it."

When this information surfaces—when leadership sees that conflict resolution is happening unofficially, or mentorship is occurring in shadow channels, or priority-setting is being done invisibly—the organization faces a choice. They can ignore it (letting Hidden Factories progress toward E and F). Or they can consciously engage with what's emerging.

This conscious engagement is what Deep Democracy calls "cycling."

In Deep Democracy, cycling happens when the same issue, behavior, or tension keeps reappearing in group discussions—typically three or more times. Cycling signals that the group is circling around an unspoken edge: something important that nobody has named yet.

Rather than treating cycling as a problem to eliminate, Deep Democracy practitioners treat it as information to follow. The cycle is the system trying to surface something crucial that consensus reality is avoiding.

When a group starts cycling, the Deep Democracy facilitator does two things:

First, they mark it explicitly. "I notice we're cycling on this same issue. We've been here three times now. That's not random. It means something important is being avoided."

Second, they invite the group to enter it consciously. "Let's slow down. Let's talk about what we're not yet saying. What's at the edge of what this group is willing to acknowledge?"

Applied to Hidden Factories: An organization starts cycling when the same structural gap keeps reappearing in different forms. Workers create informal mentorship because there's no formal structure. The organization adds a mentorship program. But workers still create shadow mentorship for things the program doesn't cover. Workers create informal priority-setting because clarity doesn't exist. Leaders insist priorities are clear. But workers keep inventing unofficial systems to figure out what actually matters.

This cycling is not a failure. It's the organization's attempt to surface what it won't officially acknowledge: "We have systematic structural gaps, and we're depending on workers to compensate for them."

When leadership marks and enters this cycle—when they stop pretending the structure is adequate and start asking what's actually needed—the cycle can shift. Not disappear, but transform from unconscious repetition into conscious processing.

Stage D and the Tensegrity Condition

What does "holding the Four Batteries" actually mean at the structural level? It means maintaining tensegrity. When a worker begins to extend themselves at Stage D—taking on work the organization's structure doesn't account for—they become like an expanding strut. The question is whether the organization provides continuous cables: recognition that this is happening, ongoing monitoring of what's being carried, and formal integration of the work into the organizational structure. With continuous tension held, the extended system cycles back down to healthy stages B and C. The work becomes visible, bounded, and supported. Without it, the cables snap. The worker extends further without restraint, the organization remains unaware of its dependency, and the system collapses toward fusion and silent harm.

Stage D is the inflection point where the tensegrity condition becomes explicit. The worker has begun extending. The system now faces a choice: will the organization maintain the cables?

Path A (Continuous Tension): The organization recognizes the worker's extension, monitors what they're carrying, and integrates it into formal structure. Continuous acknowledgment and support create the cables that hold the expanding strut in equilibrium. The system remains in dynamic balance, batteries stay charged, and the worker's extended capacity becomes organizational capacity. The cycle can then descend back to healthier stages where less extension is needed because structures are in place.

Path B (Broken Cables): The organization ignores the extension, normalizes the workaround, and leaves the worker to fend for themselves. Without organizational recognition and monitoring, there is no continuous tension. The strut extends further without restraint. The worker's identity fuses with the system they've created. Silent harms accumulate in the organization—undocumented processes, single points of failure, dependency risks that no one officially acknowledges. The system appears to work because the worker is compensating. But the cables are broken. Eventually, the system collapses catastrophically.

When we talk about Stage E—where Hidden Factory ownership calcifies into identity—we're describing something deeper than psychological attachment. We're describing a developmental regression.

Robert Kegan's core insight about human development is deceptively simple: growth happens through subject-object shifts. Healthy development means learning to see things you were once identified with as objects you can examine and change.

A young child is subject to their emotions—they ARE their anger, their joy. They can't see emotions as separate from the self.

As they develop, emotions become an object. "I'm experiencing anger. I can understand it, express it, choose how to respond to it." They're no longer fused with the emotion.

This subject-object shift—from being the emotion to having an emotion—is what developmental growth looks like across every domain.

Applied to Hidden Factories: